We all make mistakes – even the best of us. What sets us apart is how we respond to those mistakes. For companies and organisations, these are the situations when corporate ethics are put to the reality test.

We all make mistakes – even the best of us. What sets us apart is how we respond to those mistakes. For companies and organisations, these are the situations when corporate ethics are put to the reality test.

A few weeks ago, United Airlines copped a lot of unwanted publicity for losing a ten-year old girl who was travelling, unaccompanied, from San Francisco to attend a summer camp near Traverse City with a change in Chicago. Her parents had paid a $99 “unaccompanied minor” surcharge and the girl had been told that she would be accompanied at all times at by someone wearing a United Airlines badge. However, in Chicago nobody showed up to accompany the girl, and as a result she missed her connection. Worse, her parents were not informed and only found out when the summer camp called them to say that she was not on the flight.

From there, the story gets even worse. The frantically worried parents were repeatedly fobbed off by United employees in call centres in India who first falsely told them that their daughter had made the flight, and then that there was nothing they could do. Only a plea to a female employee’s maternal instincts produced any results as that employee, who was just finishing her shift, succeed in locating the girl in her own time and connecting her on the phone to her parents. By then she had been on the ground in Chicago for two hours.

The girl, it turned out, had made repeated attempts to ask the United ground staff about her connection, but had simply been told to wait. When it was clear that she had missed her flight, she asked them if anyone had called the Camp to inform them. She was told “yes, we will take care of it” – but nobody did.

There were further frustrations – the girls bags were lost and it took more hours on the phone and two wasted trips from Camp to the airport (in each case, after being assured that the bags were on the flight) before the bags finally arrived on the third day. When the parents attempted to make a formal complaint they encountered an uncaring bureaucratic process. Only when the story was picked up by a TV reporter did United seem to care and respond to the parents complaints. (Read the whole story here >> )

Contrast this horrible story with another case of an airline losing a child. In his book Do the right thing, James F Parker, former CEO of Southwest Airlines writes:

I recall one snowy night in the Midwest. It was the night before Thanksgiving. When one of our planes landed in Chicago, it had one more flight scheduled for that evening, to Detroit. In Detroit, the plane would sit in the snow and the crew would seek the warmth of a hotel room until Thanksgiving morning.

In Chicago, all the Chicago-bound passengers got off – all except for one young girl who was confused about where she was. The plane reloaded and took off for Detroit with the young girl still on board. When it arrived, all the Detroit-bound passengers got off-except for the young girl, whose family was now in a panic in Chicago wondering where their daughter was.

It was our mistake, no doubt about it. And when the captain figured out what had happened, he knew what he was going to do about it. He didn’t ask for permission; he just did it. He asked his flight crew to jump back on the airplane and told the Detroit station to call Chicago to let the girl’s parents know their daughter was coming. I don’t know how much money that unscheduled round trip between Detroit and Chicago cost us that night, but I sure was proud when I heard the story. Once again, our people did the right thing.

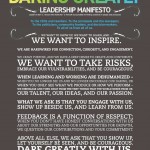

The thing that really stands out to me from Southwest airlines is that the employees felt both responsible and empowered to act. Parker refers to the “one overriding plea to all our people – when in doubt, just do the right thing. It may be a somewhat subjective standard, but it usually led to good results. It required our people to use their heads. It required them to understand what our company was about. Sometimes it drove them to make decisions from the heart.”

That sense of empowerment is a big deal. No doubt United Airlines has a wonderful corporate mission statement somewhere, or a lofty-sounding statement about the service that customers should expect. Similarly I doubt if United Airline’s employees are all uncaring as people. But somehow the corporate culture made them uncaring as employees. And in that culture of disempowerment it is impossible for the good values of the mission statement to be translated into action.

In another book, Lead with Luv co-authored with Ken Blanchard, Colleen Barrett, President Emeritus of Southwest Airlines writes: “When our People realize that they can be trusted and they’re not going to be called on the carpet because they bend or break a rule while taking care of a Customer – that’s when they want to do their best. Our People understand that as long as the Customer Service decisions they make are not illegal, unethical, or immoral, they are free to do the right thing while using their best judgement – even if that means bending or breaking a rule or procedure in the process.”

“Do the right thing” cannot work as a code of corporate ethics – in fact it could almost be an anti-statement of corporate ethics. Instead it recognises, as Seth Godin has pointed out, that there is no such thing as business ethics. Only people can have ethics and if we want them to use them they have to be empowered to do the right thing as it occurs to them. Each person will interpret the situation slightly differently and management has to be OK with that and back the decisions made by the guys on the front line of customer service even when they are different to the decisions that management might have made.

Of course key to this is hiring the right people. Southwest takes this very seriously. In fact it is statistically harder to get a job at Southwest than to get into Harvard. But their policy is “hire on attitude and train for skills”. They are less concerned with people having an impressive list of qualifications and experiences than they are at having the right character. They are upfront about the kind of company that Southwest is and the values they share.

Many companies hierarchy of values goes something like this: shareholders first (maximise profit), customers second (“the customer is always right”) and employees last. Southwest turns this on its head. Employees come first – they are like family. And in a situation where a customer is making a rant against an employee the manager’s default position will be to back the employee. The customer is not always right! (Though if, after investigation, the employee has treated the customer badly, this will be put right and the customer treated fairly.) The result of trusting and valuing employees means that on the whole, customer service is exceptional. Customers rave about the airline and this translates to bigger profits and happy shareholders. In the year after 9/11 Southwest was the only US airline to make a profit, and they did this without laying anyone off or cutting employee’s wages or benefits.

The lesson of these stories is that when it comes to customer service, real value is delivered at the level of personal ethics – individuals doing the right thing – rather than corporate ethics. Smart companies will harness this by hiring and empowering ethical employees.

Mike Lowe

Helping individuals and teams get into flow